U-Series Geochemistry and Comminution Dating

U-Series Geochemistry

Within most geologic materials (e.x. rocks and sediment) there are small amounts of the element uranium (U). The isotopes that are common in nature are 238U and 235U (isotopes are atoms of an element with different masses determined by the number of neutrons in the nucleus). For U-Series geochemistry, we focus on 238U because it is both the most common isotope of U (>99% of natural U is 238U) and its radioactive decay series is well-suited to answer some of the questions we ask about the timescales of geologic processes.

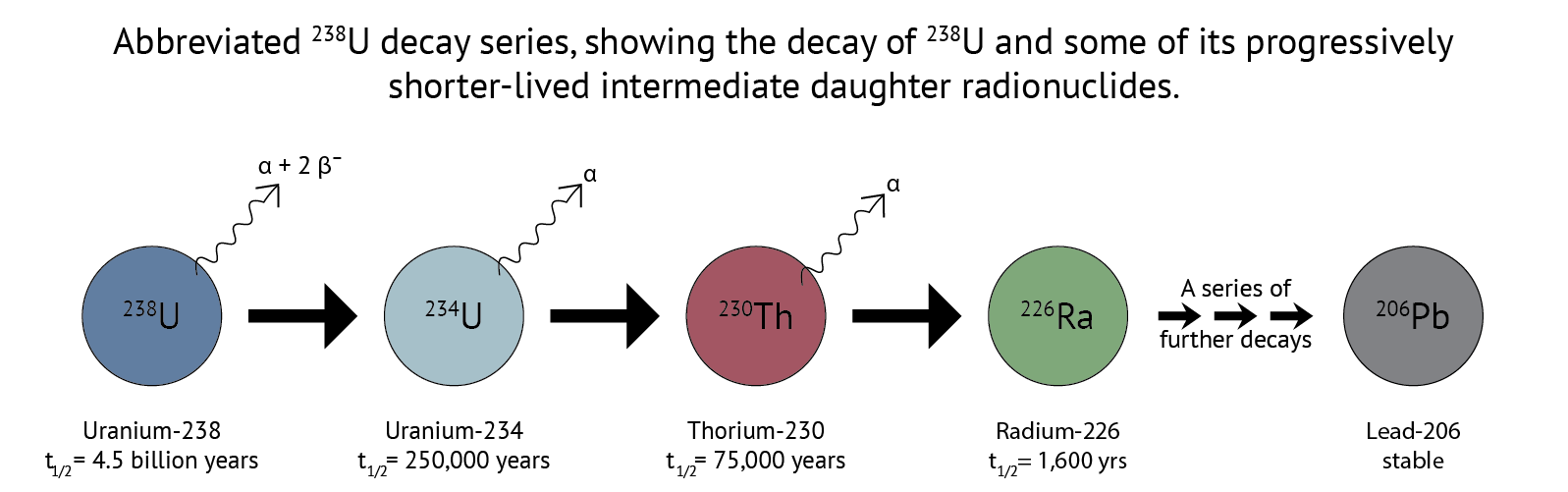

As the radioactive isotope 238U decays to 234Th, it releases a particle called an alpha (α) particle. An α particle is actually an isotope of helium – 4He. This 234Th shortly decays to 234U by the release of two β– particles, also known as electrons. This 234U will hang around for a while before going through two more α decays to produce 230Th and then 226Ra, which each hang around for progressively shorter periods of time due to their respective half-lives, eventually reaching the stable daughter isotope of 206Pb. In the case of U-series geochemistry, I am really only interested in these first 4 “intermediate daughters.”

A brief note on half-lives: The rate of radioactive decay is probabilistic: a specific 238U atom will decay probably, but not necessarily, on a given timescale described by the half-life (t1/2) of the radioisotope: the time it takes for half of the atoms to decay into the daughter isotope. Although there is no guarantee that any individual 238U atom will decay at a given time, when you have lots of atoms they behave as a group in accordance with that probabilistic behavior. In short, we can trust that the half-life is accurate for the U-Series isotopes we study.{: .notice}

If we think of each of these isotopes as a leaky bucket full of that isotope, then we can imagine a bucket of 238U that leaks into a 234U bucket. The daughter buckets (234U, 230Th, 226Ra) are continuously being filled by decay of their parent radioisotope and leaking by decay into their daughter isotope. If you leave the system alone for a long time, the rate of filling (production) becomes balanced by the rate of leaking (decay) and the relative size of each reservoir reaches a steady state, called secular equilibrium.

U-Series Comminution Dating

Comminution is the term used to describe the reduction of larger particles into smaller particles. The premise of comminution dating is to provide an age for the timing of particle comminution by relying on the U-series secular equilibrium that develops in old (>1.5 million years old) rocks and the physical effects of particle comminution.

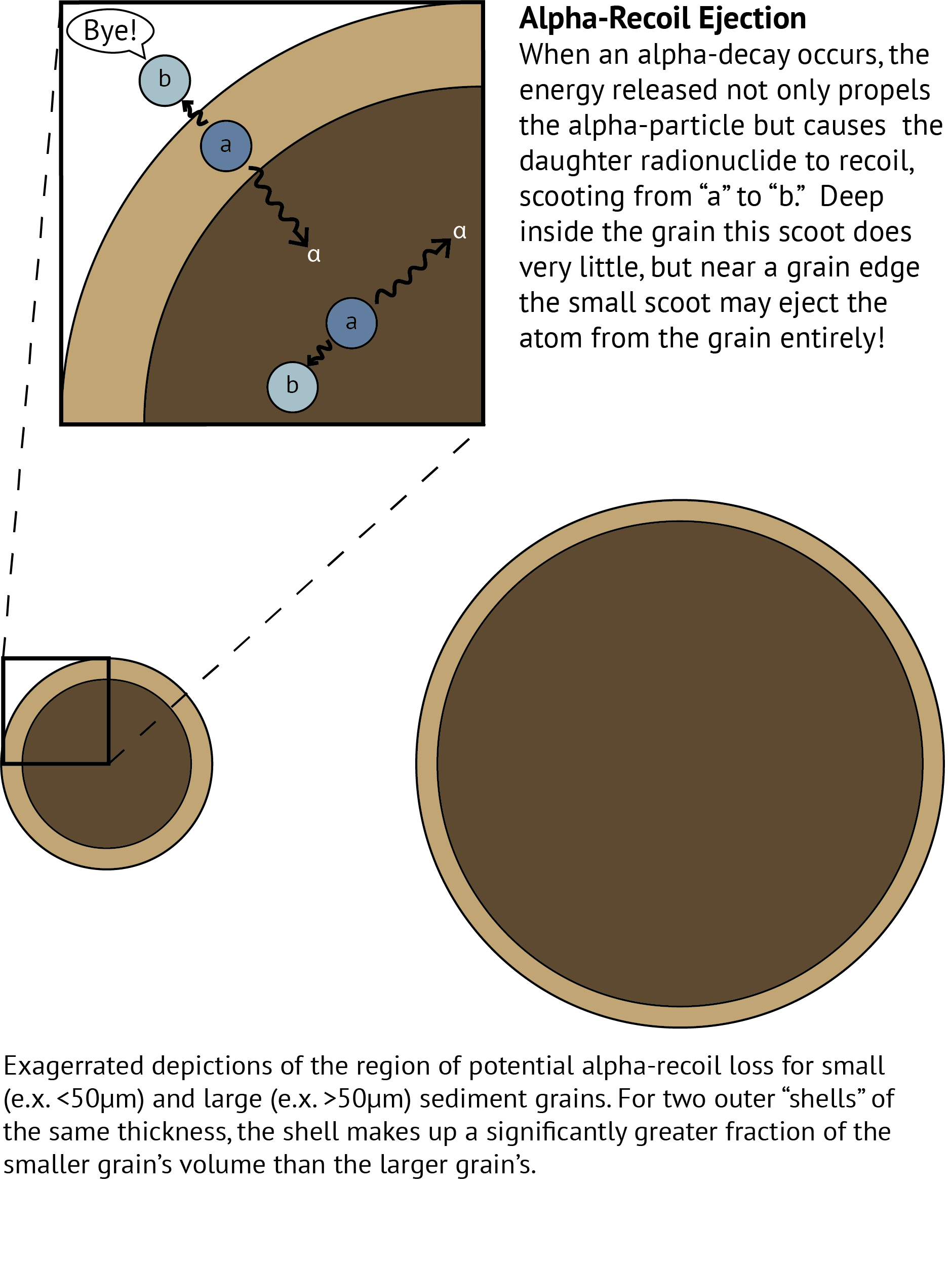

Assuming that your bedrock or coarse sediment is in secular equilibrium, loss of the U-series isotopes by α-recoil will result in disequilibrium. As explained in the image below, α-recoil loss decribes the ejection of a radionuclide from its host sediment grain as a result of the “kick-back” or recoil experienced by a radioactively decaying atom when it undergoes α decay. Over the course of time the repeated ejections of U-series radionuclides will result in an increasing signal of isotopic disequilibrium.  At sufficiently small sizes (<50μm, 50 millionths of a meter, or “silt” sized), particles of rock are small enough that the effects of alpha-recoil loss become large enough for us to measure. Because smaller grains also have smaller volume, the volume of an outer shell of α-recoil loss takes up a much greater fraction of a small grain’s volume than it does a large grain. Although alpha-recoil loss occurs at the surface of all sediment grains, the disequilibrium that develops will be much more pronounced and therefore more easily measured in small grains.

At sufficiently small sizes (<50μm, 50 millionths of a meter, or “silt” sized), particles of rock are small enough that the effects of alpha-recoil loss become large enough for us to measure. Because smaller grains also have smaller volume, the volume of an outer shell of α-recoil loss takes up a much greater fraction of a small grain’s volume than it does a large grain. Although alpha-recoil loss occurs at the surface of all sediment grains, the disequilibrium that develops will be much more pronounced and therefore more easily measured in small grains.

In U-series comminution dating, we rely on this process of alpha-recoil ejection to serve as a clock. When a new sediment grain is produced by comminution, fresh surfaces in secular equilibrium are exposed and the clock starts as daughter nuclides are lost from the grain edge by recoil loss. Our “comminution clock” ticks forward as U-series radionuclides continuously decay with time, are ejected by α-recoil, and the degree of disequilibrium increases. The greater the degree of disequilibrium, the older the “comminution age” of the sediment grain. Since each of the intermediate daughter radionuclides in the 238U decay series decay on different timescales, we have the ability to measure and resolve the timing of comminution on timescales ranging from thousands of years to about 1 million years.

For those looking for a more in-depth treatment, much of the theory of U-series comminution dating was outlined in DePaolo et al. (2006).